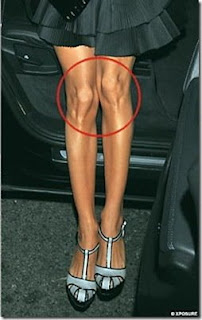

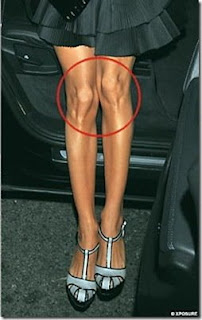

It’s widely believed that knee cartilage doesn’t heal itself. A “when it’s gone it’s gone” type of mentality. However, Egoscue believes differently. We believe that the body has an amazing ability to heal itself. For example, when you break your leg, it doesn’t stay broken, when you cut your arm, it doesn’t stay cut, etc. We believe that cartilage has the same healing ability and stimulus-response characteristic that the rest of the body has. The pain in the knee isn’t there because there’s something wrong with the knee or meniscus, rather we need to find the cause of the pain and treat that. Because Egoscue focuses on the position of the knee rather than the condition, we are able to focus on the misaligned knee capsule as the cause of the pain. Notice the position of the knee in this picture:

There’s nothing inherently wrong with this person’s knee (or anyone’s knee for that matter), but with the knee being in this position (and their left knee is much more compromised than their right knee) they are headed for trouble at some point in their life. They could end up with a torn meniscus, “headed for a knee replacement”, or chronic pain that has nothing to do with the knee at all. The body is a unit, and the knee bone is connected to the hip bone, remember?

So, knowing what we know about the body, that it can and will heal itself, I was ecstatic to read this article. It might just be the start of proving what Pete Egoscue has said forever: The knee, its makeup, and its design are no different than the rest of the body. It’s not poorly designed, it just gets into the wrong position, and a compromised knee position is most likely a painful knee position. If you get the knee in the right position the pain will be eliminated and the knee can start its healing process. Keep moving and stay healthy!

Egoscue Nashville—————————————

Exercise May Improve Cartilage in Arthritic Knees

‘The changes imply that human cartilage responds to physiologic loading in a way similar to that exhibited by muscle and bone, and that previously established positive symptomatic effects of exercise in patients with OA may occur in parallel or even be caused by improved cartilage properties.’Moderate exercise may improve the physical composition of joint cartilage in patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA), according to a study published in

Arthritis & Rheumatism.

Osteoarthritis is the leading cause of disability among adults. Along with early diagnosis, moderate exercise is one of the most effective ways to reduce pain and improve function in patients with OA of the knee and hip. Yet, more than 60 percent of US adults with arthritis fail to meet the minimum recommendations for physical activity.

Because OA results from “wear and tear,” the commonly held belief has been that exercise will not strengthen joint cartilage and may even aggravate cartilage loss. Until recently, investigators were unable to put that belief to the test. Radiographs, the technology typically used to measure OA’s progression, could not assess cartilage damage until it was severe.

Now, thanks to advances in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), it is possible to study cartilage changes earlier in the course of OA.

GAG Content

Two researchers in Sweden, Leif Dahlberg, MD, PhD, and Ewa M. Roos, PT, PhD, used a novel MRI technique to determine the impact of moderate exercise on the knee cartilage of subjects at high risk for developing OA — middle-aged men and women with a history of surgery for a degenerative meniscus tear.

Drs. Dahlberg and Roos recruited 29 men and 16 women aged 35-50 who had undergone meniscus repair within the past three to five years.

At the study’s onset and follow-up, subjects from both groups underwent MRI scans to evaluate knee cartilage. The technique used focused specifically on the cartilage’s glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content, a key component of cartilage strength and elasticity. Subjects also answered a series of questions about their knee pain and stiffness, as well as their general activity level.

Subjects were assigned randomly to an exercise group or a control group. The exercise group was enrolled in a supervised program of aerobic and weight-bearing moves, for one hour, three times weekly for four months.

Thirty of the original 45 subjects — 16 in the exercise group and 14 in the control group — completed the trial and all post-trial assessments.

Compositional Changes in Adult Cartilage Compared to the control group, subjects in the exercise group reported more gains in physical activity and functional performance. Improvements in tests of aerobic capacity and stamina affirmed the self-reported changes.

What’s more, MRI measures of the GAG content showed a strong correlation with the increased physical training of the subjects who regularly had participated in moderate, supervised exercise.

“This study shows compositional changes in adult joint cartilage as a result of increased exercise, which confirms the observations made in prior animal studies but has not been previously shown in humans,” notes Dr. Dahlberg.

“The changes imply that human cartilage responds to physiologic loading in a way similar to that exhibited by muscle and bone, and that previously established positive symptomatic effects of exercise in patients with OA may occur in parallel or even be caused by improved cartilage properties,” he adds.

The study does have limitations — its small sample size and narrow focus on meniscectomized knee joints — and makes no claims for predicting the long-term effects of exercise on cartilage.

However, the researchers maintain that its conclusion is worthy of serious consideration. “Exercise may have important implications for disease prevention in patients at risk of developing knee OA,” say Drs. Dahlberg and Roos.

by Rita Jenkins